Blue Apron Food, for Thought

As investors across a variety of food service related companies (Tovala, Tock, and GrubHub), we at Origin Ventures are constantly looking to further our understanding of this trillion dollar segment of the US economy. We are also avid eaters ourselves, so whether it is fine dining (Tock), on the go (GrubHub), or at home (Tovala), the future of this industry isn’t just financial, it’s personal as well. That’s why we got excited at the prospect of Blue Apron’s IPO – it represents a unique opportunity to dive into the details of a budding industry giant and analyze what the future may have in store.

From the outside, one of the concerns you often hear discussed about Blue Apron (and similar competitors) is that Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) is too high and user retention is too low. After combing through their S-1 (representing 2014 to end of Q1 2017) with this hypothesis in mind, we found a treasure trove of data. While much of the nitty gritty is obfuscated, there is still a lot to be gleaned.

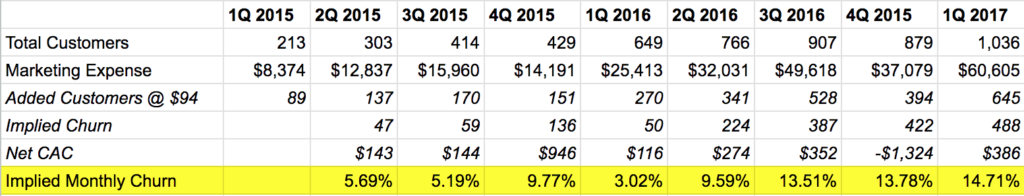

To understand CAC and churn, we calculated the following:

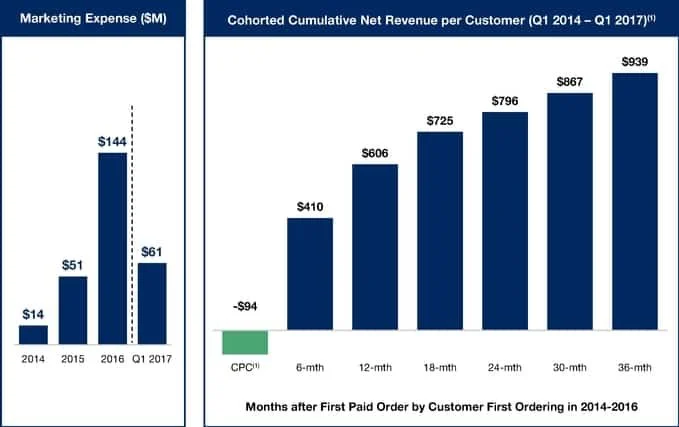

Total marketing expense over their reported time period was $270M. Average CAC for all customers ever acquired was $94. From this, we can infer that they have “acquired” roughly 2.9M customers over the the last 3.25 years.

As of March 31, 2017 they have just north of 1M total active customers.

At 1M active users, the $270M marketing spent to date really implies a blended CAC of more than $250. This is 3X higher than the $94 to which they compare their LTV, and also implies an all-time customer churn rate of roughly 64%.

We can view this on a quarterly basis (assuming a constant $94 CAC), to see that churn is getting worse over time.

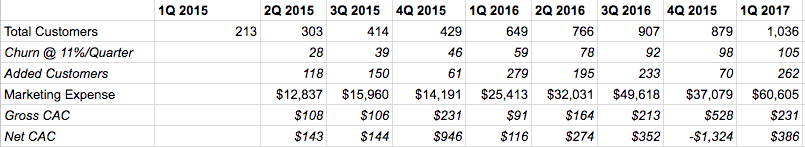

Knowing that a constant CAC is unlikely, we wanted to break down the 64% churn using a different approach. To do this, we then broke down each of the “cohorts” to see if we could discover any additional insights. (Note that this isn’t real cohort analysis because each group starts at a different point over the last three years, so there is some approximation going on. To that end, we used the weighted average of quarterly revenue per customer of $247 for our analysis).

Overall this implies a monthly churn number of 3.5% (across the whole group), which means the company is losing ~40-50% of its customers every year. To grow, the company has to first “replace” these customers and add a whole bunch more. The same caveats as above apply, but we took this one step further to try and get better insights into exactly how acquisition cost has affected the number of users being added and retained, and how that has changed over time.

At first glance, this paints a slightly rosier picture in that the numbers imply that Blue Apron only needed to add 1.4M users to grow by 800K over the last 2 years (although the 36-month cohort does have churn of 68%). However, this also shows us that not only does the company need to have a substantial user acquisition engine in order to maintain its growth trajectory, but that the cost of acquiring users (Gross CAC) is generally increasing over time. A possible explanation is that the low-hanging fruit has been picked, and now customers will get incrementally more expensive, and will likely have incrementally lower retention. This is demonstrated by the increase in “Net CAC” in the last year – implying that churn is higher of late than the fixed 11% we assumed for our Gross CAC analysis.

Putting all of this together illustrates the difficult unit economics Blue Apron may be facing. The 3.5% churn implies a customer lifetime value of roughly 28 months. Also gleaned from the S-1, the 30-month “cohort” has an LTV of $867 and COGS are around 68% (admirably improved from the 92% in 2014). That means that the gross profit of a single customer is roughly $275. With CAC sitting now in the mid-$200s per customer, that leaves only $75 per customer to pay for the operations of the company. With 20% of revenue being spent on “product, technology, general and administrative”, it’s tough to envision how it turns a profit without a combination of improving retention, declining CAC, or lower COGS/costs .

This suggests a confirmation of Origin’s hypothesis: Blue Apron struggles with acquisition cost and churn. While the product is compelling for many, the single largest concern we’ve heard from former customers is that the time savings is not as high as they’d hoped given the cooking and cleaning that is still required. Blue Apron meals pile up as a result, and it starts feeling like homework and not worth the money.

What Blue Apron has proven is that consumers are clamoring for a convenient, fast, and fresh solution that fits into their daily lives better than constant trips to the grocery store, eating out, or restaurant delivery every night. The solution has to be dead simple, and avoid the chores of cooking and cleaning for every meal. This is how we arrived at our investment thesis behind Tovala, which we will detail in a future post.